Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara - President, Prime Minister

Ratu Mara was born in the south-eastern Lau island group into an aristocratic family with Tongan and Samoan connections, he held the titles of Tui Lau, Tui Nayau and Sau Ni Vanua, an impressive pedigree reinforced by his wife's chiefly rank in her home island of Viti Levu.

Dutifully responding to Fijian and British arrangements preparing him for leadership, Ratu Mara did well at schools in Fiji and universities in New Zealand and UK. An accomplished sportsman, he could reach across cultures and had earned the respect of the communities of Fiji as Leader of the country's dominant political party, the Alliance.

No-one was better equipped to lead the country into independence, and at the age of 50, he accepted the task as an inescapable chiefly duty. The last of his leadership roles in Fiji politics was as President of the Republic from 1993 to 2000. Interviewed by Ian Johnstone in 1995, Ratu Mara explained he'd once hoped for a very different career as a doctor.

Transcript

Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara: Otago Medical School I always thought of as one of the best years of my life.

I played a lot of sport, made a lot of friends, and was able to get through my exams without much difficulty… eventually played for Otago in cricket and rugby, in athletics I got a NZ universities record for the high jump – and won the drinking blue in Dunedin… I created a record 1.8 seconds, which stood for some time, and it was a bolt out of the blue when I got a letter from Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna. They'd been discussing my future with the Warden of Wadham College, Oxford, Mr. Bowra. They thought I'd be more useful to Fiji if I left medicine and studied economics and immediately after that, "I'm sorry I will not be hearing from you but you are to report at Wadham on October 13th. Your passage will be arranged by the BNZ in Fiji and I hope you will be here in time to attend"

I arrived prepared for the course and went up to see Mr. Bowra. "Ah, yes, Mara, you're Sukuna's nephew…we did decide you should read economics, but I've contacted him and you should read modern history – best course for you. So there you are". So I said "Modern History…how long will that take?" "you must take the Honours course, that will take three years".

Ian Johnstone: That was training you to come back and be part of the colonial administration here?

KM: Any part of the empire…

IJ: You could have gone to Asia, Africa…

KM: Malaysia and Kenya were highly paid places and I think the best of us go there, and I probably would have liked to go there for three years or so, but they found out I came from Fiji, and I had to come here!

IJ: Where were you posted on first appointment?

KM: Where was I posted? I was Governor of Navua! Mr. Sykes said "You're going to be the Governor of Navua, if you do well, you'll get a pat on the back… if you don't, you'll get a kick in the BTM"!

IJ: Was there any sense of awkwardness? Here you were, serving the colonial power?

KM: No – I enjoyed it and I thought the people enjoyed it, too. I was very proud to sit there as a magistrate (third class, in small letters). Fijians called me the "Magistrate of the Europeans".

IJ: Did you have a sense here in the fifties, that it had to end, this colonial period?

KM: Surprisingly, I didn't have that feeling, because we think we are not going to become independent. We were part of the Queen's regnum; we were happy – why should we change things?

IJ: You must have sensed the wind of change, coming mostly from overseas?

KM: Yes, the winds of change… we heard you could see it on television by CNN at that time, but we thought it was remote warning, a hurricane warning, that would never come to Fiji. I belonged to the school that believed we should not be parted from the United Kingdom, and there were countries like the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands who are on their own but yet they are part of the UK - and I think there are still some small islands in the West Indies… I think the Virgin Islands is still a virgin!

IJ: So was a serious proposal put forward that Fiji might adopt that status?

KM: Yes, that was our first reaction. We said why should we… we ceded our islands, as far as we're concerned, we've given the authority – how can we bring it back? This is not chiefly.

Gifts for the chiefs

IJ: This was the Fijian view. Did you sense that the Indian community in Fiji was more anxious that the UN should come in?

KM: Yes, the move to get the UN to come in was in response to their desire. In the Legislative Council they were banging the table, saying we should be independent and have a common roll; and there were remarks against CSR (Colonial Sugar Refinery) and big firms who were "exploiting the people". I felt in the early days that was the legitimate reaction of a people who've been badly treated by their employers. They want to get rid of them. It only came later that they really wanted those people to move out and leave us. It wasn't until the Kisan Sangh wanted to strike and stop sugar milling that Fijian members got together and formed the Fijian Association and declared support for government and CSR. That's how our first political organization started.

Election poster, 1987

IJ: Was this when the Alliance was formed, sir?

KM: The Alliance was formed before the 1965 conference in London.

IJ: There was a position to be represented there. How did you enjoy those visits to London?

KM: I enjoyed both conferences. Of course, everything was new. At the time I didn't realize that the destiny of my nation was being discussed. I was trying to score points across the table from the other people… but we did a lot of work as an Alliance. We studies all the constitutions of all the colonies from India onwards… put them on the table and said "We like that… but not that" By the time we finished we thought we had a good constitution, and put our work down and the others just criticised it. They had no alternative.

IJ: This was to be the essence of the 1970 constitution? I suppose your domestic opposition, all they could shout was common roll… Did you ever think a common roll was a starter?

KM: No. Swamping was at the back of mind if we had a common roll, and the population figures were changing… one was moving up, the other was stationary or being surpassed and who knows, in ten years time it was indicated that we would be a minority in our own land.

IJ: As you say, the destiny of your nation being resolved overseas, needing constant attention, and also, had you just introduced the Member system? Did that come later?

KM: The amazing thing was I think we were the first country that became independent, in the 1970s, without a common roll. All the others had common roll.

IJ: Did you know of any other colonies moving to Independence who were as… hesitant, who would perhaps have preferred to stay within? Were you able to consult with them while you were drawing up your plans, seeking their advice?

KM: We did a round the world trip and the first country we went to was the United States and we were entertained by a Mr Samuels, I think, of the State Department and over drinks he asked where we were going. I told him from here to the West Indies, to Jamaica, Trinidad, Guyana, then on to England, India, Malaysia, Singapore. "So you're going to the old colonies". "Yes" I said "that's why we're starting right here!"

IJ: How did you find that (1960s Member Cabinet period) sharing when you had fine people with you, John Falvey, AD Patel, but in a way you were political enemies. How did that work?

KM: We were political enemies but there was a strong undercurrent of rivalry, you know, I'm going to do my job better than he's going to do his, a friendly rivalry. A lot of consultation in the Council meetings.

IJ: It's hard to think that you didn't have very good social connections, so when it was over would you and Patel sit and talk in a friendly way about what went on?

KM: No, I didn't have a lot of time talking to AD Patel outside working contact but there was some relationship between AD Patel and I because during the difficult times of the war when there were cane strikes, 1943-44 when I came back on leave, Ratu Sukuna used to take me round to talk to AD Patel and SP Patel and have meetings with their group and I got to know them. I found out later of course that he went to the London School of Economics…

IJ: One of your worries must have been that a Westminster-style constitution (with a government and an opposition) would fracture the country along racial lines? And yet, because we were a British colony, you had to go the Westminster way.

KM: It didn't have to fracture it – it was already fractured. We had already the Indian view and the Fijian view. They were not co-incidental and therefore they were in opposition. It was not violent but it was already fractured.

IJ: The Westminster system wouldn't help to heal that fracture, or pull people across it.

KM: It was the only Parliamentary system that I know. If we were to move to independence, it must be along this system. There must be an opposition and a government side.

IJ: In the late 1960s, a difficult but exciting time, you were faced with the inevitable, and a huge task for you. You had to reassure the Fijians, overcome your political opponents, satisfy the pressure from outside. Did you wish you weren't there?

KM: No. When I started the Alliance, I thought I'd found the solution; get all the races together and we could run Fiji with all the races well represented and playing their role in the governance of the country. But when I failed to attract Indians to my side, and those who came were regarded as traitors by the rest of them, that was the time when I think the scales fell from my eyes, so, well, what's the next solution. I was still looking at a way of getting people together… and in 1970, the Alliance.

IJ: You did find the solution. Tell us about the business of persuading. You must have had to go out and pull people towards a solution that maybe their tradition didn't want them to?

KM: I found people who were willing to come. At first the novelty of the ideas brought a lot of people in but I must admit this, when we ourselves were not clear in articulating the needs of all the races, because we were feeling our way… what would the Fijians say about this… and what would the Indians say about this…? They wanted to know exactly – what about our desire for equal representation? We couldn't come up with that. I had to say, we have to go now to the Council of Chiefs… I think we didn't play our role as well as we could have done.

IJ: It seems to me that in spirit the various communities of Fiji wanted to work together.

KM: I believe so because we very nearly… I'll just go ahead another ten years… in 1981 I proposed a government of national unity before the election because I wanted the two parties to agree on that and then go to the election and say after the election we'll have a government of national unity. To me that would be the best construction of two different groups. There's a lot of detail to be filled in. I assumed it would be a Fijian Prime Minister and an Indian deputy and more or less equal numbers of Ministers, each with particular expertise – going back to AD Patel, John Falvey…

IJ: The three-legged stool. Did you worry that the 1970 Constitution was too complicated, that people here wouldn't understand? Didn't it involve voting four times?

KM: As I said, much of our work wasn't well done. One was to translate that 1970 constitution into good Fijian. We didn't succeed in doing that, but for the constitution, I believe it was the best Fiji could have – and I still think that today.

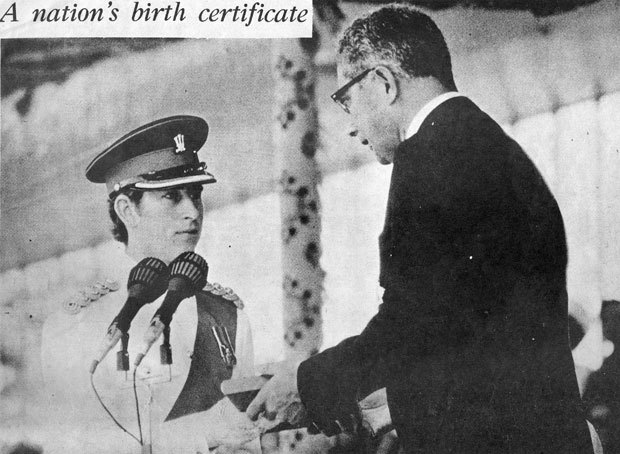

IJ: You accepted Independence on October 10, 1970. Can you reminisce about that day on Suva's Albert Park?

KM: That was a great day. We decided that we shouldn't follow the others by getting up at midnight when people are rather sleepy, to see one flag going down, another going up. We decided to lower the British flag one day, with a Retreat, then at 10 the next morning, raise the new flag. I still feel it today, the thrill… the expectation of great things to come… all the people of Fiji there… all the religious people and bodies were there… and the Prince of Wales handing over to me, and I accepted and knelt down and performed the cobo. Most heartwarming day was the Sunday when we had the ecumenical service with all the religions there, Christian, Muslim and Hindu and I think all those religious leaders really meant what they said when they were coming together to form a new nation.

Prince Charles and Ratu Mara at Albert Park, Suva on 10 October 1970

IJ: One of the very affecting things was to continue your last Governor as your new Governor-General. Was that done because of its significance, or because of the person, or both?

KM: Personality counts a lot. Foster was a gentleman and we thought he could carry on and if there is any conflict, he could tell us. He was very free and open with his advice. Anyone who wanted to discuss matters could do so.

IJ: Presumably that appointment had the consent of all your colleagues.

KM: Yes. I had a wonderful person, a great facilitator, in my early leadership – Ratu Edward Cakobau. He seemed to find the solution in any difficulty. People looked to him. In cases like the appointment of a Governor-General I would talk to him and he'd say "Leave it to me. Don't worry, I'll see the others".

IJ: That was true in his whole life. We honour him. In those early days, one could see you reaching into the communities and exposing yourself and your commitment to Fiji to Indian farmers, Muslim groups, whatever. Was that a deliberate…?

KM: No, that was the result of my District Officership. As DO I had to manage Fijian and Indian schools, although Indians at the time were starting their own schools, we liaised with them about government subsidies and health. I was chairman of the Native Land Trust Board District Committee, a very important committee. It felt the pulse of the Indian people as far as land tenure is concerned. We received applications for new leases and for renewal of leases; we had to go into their homes. For the first time I realised you can't just terminate a lease and move people out – because there's a school and a temple and people would be completely lost if you removed them from that environment. It was a great lesson in human affairs.

IJ: You seem always to have been confident and comfortable in Indian communities.

KM: I've found no difficulty whatsoever, surprisingly. I cannot speak Hindi, I understand some words and the drift of the conversation – but I felt my District was my kingdom and I must serve it… I think Indians like firm leadership and I can give it to them!!

IJ: In 1971, I remember my children – all of us – learning to sing the national anthem, with excitement. You must have been very proud of what was done in those first five years. Were you conscious of leading by example? Were you working terribly hard – or did it come easily?

KM: No. Right from the early days I've thought that even if you can't talk well, at least your example can be more loquacious than you are. Leading by example was the greatest thing I have, I think.

IJ: It certainly worked. To offer a humble example, soon after I left here I went to South Africa to make some films. I remember being confronted with the horrors of apartheid.

IJ: I had been "a bridge-builder". It took me two days to say "It doesn't have to work like this" I have just lived in a country where it works in a completely different way. You set an example for the world then. Were you aware of that in the early seventies?

KM: I'm glad you asked that question because I attended my first Heads of Commonwealth meeting in 1971 in Singapore and in a discussion, I made a remark that we were the only multi-racial country in the world. Lee Kwan Yu pulled me up very very quickly and I very very quickly said yes, I agree, you're right! His country, Singapore was another example. I became very friendly with him. We seemed to have great empathy in discussing our development. He was all for doing things yourself and not relying on other people for help, unless there is some unique way in which only they can help you. But do it yourself and then you'll find the right people will come to help you.

IJ: Those British and Commonwealth connections. Were they very important to you in the first 10-15 years?

KM: What I admired in this man was his strict adherence to principles, and to law and order. I found that was the way you ought to run a multi-racial country. Be firm, tough, people will respect you. Different religions, different races will respect you if they know that is the way you behave. If you waver…

IJ: Again, the chiefly and the administrative were very important, I suppose, for you hold that position. Can I ask about forming your first cabinet. Was that easy? Did people fall naturally into their places?

KM: We'd formed the Alliance by then, with European, Indian and Fijian sections. I just found out who in the various races would be good for this or that. Doug Brown - former Principal of Navuso Agricultural School - what better Minister of Agriculture? Charlie Stinson, although he didn't stand for us, had been a successful businessman, so I put him in Finance. Ratu Edward was Home Affairs and Deputy. They seemed to fall into place… Attorney-General was John Falvey.

IJ: Remember chairing your first meeting after Independence? 1972, I suppose, after you'd won.

KM: We'd had cabinet meetings before that, of course. But we won and by that time we were old hands… two years of experience!

IJ: But a lot of experience at working together.

KM: We had no problems working together. Ratu Edward was my facilitator and if anything became difficult, he'd say "don't worry…"

IJ: Twenty-five years ago that Independence happened and, as we know, events with major constitutional change and the like since then. But looking back, delights, disappointments about that process of gaining independence?

KM: I have no regrets at all. I thought we were lucky to come the way we did. Many other countries had difficulties. We didn't. Mauritius is a prosperous country now, but soon after independence they had a bit of a hiccup, and we didn't have any. The Indian representatives walked out of the Legislative Council in 1968, I think, on Common Roll. We carried on. I was advised at the time not to fight the by-election when all the Indians walked out. But I wanted to test the water. I wanted to find out how many Indians will stand for me. And we had 31% I think, and that's the highest percentage of Indian support I ever had. It went right down to 8% and I lost.

IJ: It's about 50 years since the Otago days and you were looking forward to a life as, I don't know, maybe a specialist for a while but then a comfortable and very successful GP. Do you sometimes wish you were about to retire as a doctor?

KM: Time and time again I've regretted I didn't complete medicine. And I think if I did complete medicine I would have opted out of the administration, like my uncle Ratu Dovi. My ambition, as well as becoming a doctor, was to be District Commissioner and District Medical Officer at the same time for the Eastern Division. That was my ambition. When I get there Government would provide a boat and I'd visit all the islands and be a doctor and also a magistrate – what more do you want? This is Moses coming down from heaven!

IJ: But somebody determined it was going to be a rather larger scene than just Lau and Lakeba and your little cutter. The other side is that this was a contribution that had to be made.

KM: Yes. I can't say, honestly, at any time I thoroughly enjoyed this job. It has been a struggle from the day I left medicine. Particularly the contrast. When I thought I was going to slide down the slope and get a degree, and then I had to go and struggle on a subject that's such a contrast from precise, scientific studies…every book you pick up is different from the one you read next. It's been a struggle right through.

Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara