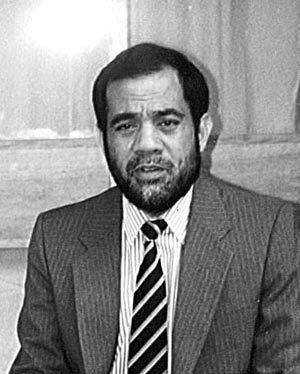

Sir Ieremia Tabai - Berititente

The country's first president, or Beretitente, was Ieremia (later Sir) Ieremia Tabai from the southern Gilbert Island of Nonouti, which he still represents in the nation's parliament. His service as Beretitente was the maximum period allowed by law, 12 years (1979–1991). An accountant qualified in New Zealand, Sir Ieremia was also Secretary-General of the Pacific Islands Forum from 1992 to 1998. He was born in 1950, and went at the age of 11 to King George V High School in the capital of Kiribati, Tarawa. In this interview with Ian Johnstone, recorded in 2011, he recalled those early schooldays.

Transcript

Sir Ieremia: We had the normal list of subjects: English, bio, geometry and geography and all the rest. In primary school we had learned how to construct sentences, a few words here and so on and it’s hard going. This is not an easy language to learn, and I am still learning now at my age! When I travel now I might hear a word on the plane and I do not understand what it means so I carry my small dictionary all the time with me.

Ian Johnstone: You were very much part of a colonial system, the British administration of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony. Were you aware of that?

IT: No, I wasn’t quite sure, because from there I was selected to go to high school in New Zealand. You know, at school you never think you're part of a bigger world. You just go there because you have to... and that’s how I used to think.

IJ: Let’s talk about how you got to New Zealand. Yet another competitive exam?

IT: Well yes, in high school I never came first place in my class but I consistently came second place. And so I was recommended to go to New Zealand and the scholarship was funded by New Zealand. I must have been good enough.

IJ: And how was that shift? From Tarawa the capital but still tiny and still forty degrees plus and hardly any rain and all of a sudden you are where?

IT: I went to Christchurch, to St Andrews College in Papanui Road. We were met at the airport by the head of the school, Ian Galloway and he took us to his home. We spent about a month and the object of the exercise was to be introduced to the New Zealand way of life.

We were taught to sit at the table and which spoon and fork to take first and so on. And you never stretch out to get something you want, always ask. These things were taught in their home before we went to the boarding school.

IJ: Who was there with you?

IT: Well I and another guy. He’s now a lecturer at the Alafoa College in Samoa, he’s my classmate.

IJ: You were a long way from home. What was it like? Did you cry? How was that adjustment?

IT: Every evening, at least when I first came, I cried in my bed, because it’s lonely, you are cut off from your home. And every week I stood at the gate waiting for the postman to come and if I didn't get a letter, I was very disappointed and I was beginning to think about all sorts of things.

It was lonely experience, particularly when your classmates are a bit cheeky to you it makes life that much harder. When I was in St Andrews College, on a sports day, we had to cycle to another school. But the problem was I didn’t have a bicycle, I couldn’t afford it. So, I was trying to avoid having to say that that I didn’t have a bike to go on. But again it one of those things I had to go through, it’s not easy.

I remember too that each seven days we were given 30c by the school and I gave 5c to the offering because we go to church every morning. And so I save 25c. And so by the end of the term I have a few dollars which I use to buy… I’m not too sure what to say! But anyway, those experiences have taught me to careful with the resource and look after yourself well and so on.

IJ: The return to Tarawa must have been an excitement. Was there a job offer when you came back home?

IT: At the time there must have been only a handful of us with a so-called degree from a Western country and so it was easy to get a job because of that. So, I was posted to the Ministry of Finance, the Treasury. And I worked there for one year only. Because the next year there was an election, because of my interest in the election, I contested the election.

IJ: On that return, you’d arrived with a BCA wasn’t it? Could you sense when you arrived home could you sense the moves towards Independence or self-government or whatever might come? Towards the end of the colonial rule.

IT: Basically it was over, they were resigned to the fact that it was over. It was just a question of organising ourselves and as I said everything is organised towards Independence. A date has been pencilled and so on.

IJ: We’re talking about the early 1970s - is that right?

IT: Yes, early 70s. When I came back, the guy was Naboua (Ratieta), he was a well-known guy, we were the new blood as it were you know. And very young. He was groomed, been in the game for many years and everyone was expecting that he would be the next leader.

IJ: Were there any people, any iKiribati who didn’t want to, who wanted to stay part of the Queen’s Realm as it’s called?

IT: It’s hard, it’s hard to find anybody who does. Because I think that the people here are by nature, what’s the word? Very quiet. And to push Independence was never based on a harsh manner. I must admit the whole process was also helped by the attitude of the British government who are very keen to call it a day and say it’s no longer fashionable to have colonies. And our role now is to get you people organised and ready to be on your own. So it was never a question of having to fight for Independence. Really our masters were very keen to leave us at any time.

IJ: And that was common of course, but not always welcome. Fiji struggled very hard to remain a colony.

IT: I could not find any evidence of any people struggling, making a move away from Independence. Accepted that it is coming, we just get ourselves organised and ready for it when it comes.

IJ: And also, I imagine having to do the best deal that you could with the British.

IT: But that was the responsibility that fell on us when we took over in 1978 I think it was, when I won the election and became Chief Minister and that full responsibility was our responsibility. So I negotiate a constitution and our financial package and all the rest of it.

IJ: Now let’s just look first can we at that constitution? What did you think about inheriting the Westminster system direct from the British?

IT: Well I must say, if you have a look at our constitution, it’s not the same as in any other constitution in the region. While we accept that we have benefited from our experience with the British, but if you read that Constitution it’s very different from what you have in New Zealand and in Australia. And I must admit I am really pleased with the result.

It’s working, our neighbours now are talking about adopting our system. One of the things I learned, I heard the prime minister of Vanuatu had lost a confidence motion, and it’s really funny when the leader is on his way to Mexico and then his friends are back home voting him out. It would never happen here. Compared to the experience of the other countries in the region, politically we are very stable and that’s because of the constitution we have.

IJ: Now also of course you are unique in that you have an executive president. How did it come about that you got the constitution that you did?

IT: We had a very extensive consultation process. I was still in parliament at that time, we had a consultation on the islands in the villages. And the result of the consultation was brought to Tarawa and we have a national constitution convention and was a result of that thing we have agreed on the nature of the constitution and with that agreed we have a Parliament and I am in there at that time. And we go through all the recommendations again. After that discussion was done we went back to our islands again and it’s after that process that we got what we’ve got now. A very extensive process of consultation.

IJ: Is that because iKiribati and Micronesian people perhaps are very good at sitting down and talking about what they want rather than being led by chiefs or swayed by orators? Is there something in your tradition that helped this?

IT: It’s possible but when we were in Parliament we took the view that you really have to look at the local element and we don’t have to be bothered about what happens in the UK or Australia or New Zealand. We have an executive president and the way he is elected is different from any other system in the world. We have the concept of a limited term which we have borrowed from the Americans and the French and the limited term is a very good idea if you ask me. Because when I was in government at that time before Independence I saw what was happening in other places such as Indonesia - the guy has been there for years and years. Even our neighbours, I don’t want to mention their names, but they have been there for years and years.

My view is it’s wrong for any particular person to be in government for too long. It’s wrong, and that’s why we have the concept of a limited term. We have a maximum of 12 years you can serve no matter how good you are.

IJ: First of all you had to decide whether you and what was then Ellice islands would stay together. Was that ever a probability you would stay together, become a nation together?

IT: The British gave them the option to remain with the Gilbert Islands or go their own way. And they chose to go their own way and I can well understand the reason. The simple reason is they feel they will be outnumbered and they will be dominated by our people and that’s why they feel they have to go on their way. When I look back I think it would have been better if we had stayed together as a country. I guess I am biased because I married a girl from Tuvalu and that’s probably a mistake of the people at that time. But it’s history now and we still get on with our Tuvalu neighbours very well indeed.

IJ: When you looked at this putting together of Micronesian and Polynesian it looked like a very colonial decision didn’t it? Oh you know, we’ll draw a line down there and then across these islands and then up the other side. But you’re satisfied that it could have worked in the long term.

IT: Yes, well I think the view is that we could have been a bigger country with a bigger voice and so on and you know they are very resourceful with those small atolls there. And they seem to be doing well. I look at the statistics and they are doing better than we are. The value of their reserve fund per capita is doing much better than we are and so on.

IJ: Another problem you had to deal with around 77/78 was that Banaba, whose island had been taken from them by the phosphate miners really, suggested they wanted to leave you and go to Fiji. What happened there?

IT: Well the Banaba thing is a long story and there is a big dispute about what the argument is. But they wanted to go their own way and we said no and that’s the compromise we have in the constitution. If you look at the constitution we have a chapter that deals entirely with Banaba and the whole intent there is that we would not be able to take away their land or do anything on their land without the consent of their Rabi Council and that chapter was really imposed by the British because you know they want to leave this part of the world with their reputation intact and they thought the best way to do that was to include a chapter in the constitution on Banaba.

Their demand to take away Banaba to Fiji didn't make sense anyway so we stick to our view that the Banabas should remain with us and I think that was a right decision.

IJ: Just the third difficulty it seemed to me that you had to overcome was what seems a pretty unfair decision that the phosphate mining would end in the very year that you became independent, therefore the main source of wealth for your colony was taken from you. Did you feel bitter about that?

IT: It’s no longer relevant in these days, we have to make the best of what we can but definitely it’s funny because definitely on Independence day we lost the main source of income and since then it’s affected the level of services we can provide. We’ve got a budget of about 18-19 million a year. And you know we accepted that, but it’s very hard. And the Minister of Finance for the budget for next year has budgeted for a decrease. And the only reason for that is because the money is going to decrease and he has no other option.

But anyway we have now what is called the reserve fund which is the main income earner for the government. It’s worth about 500/600 million Australian dollars and the interest each year we are using as a balancing item in our budget.

IJ: You mentioned earlier on sir that the British wanted to leave the Pacific with their reputation intact. But when you look at what was happening with a) how they had decided to get out and b) things with the Banabans not at all tidily done and c) the phosphate money that was denied to you, what sort of reputation did they leave in Kiribati?

IT: Well that’s for historians to ponder on. I understand that in this world you do not have permanent friends, just permanent interest. It was no longer in the interests of the British to hang around here. The best thing for them is to go back and be on their own. We accept that and we know that we have to be on our own, and just do what we can afford. That belief influenced a lot of my thinking when I came to Governmentt and the words I used a lot were self-reliance. I still believe in it, though some people may not.

IJ: When the election for Chief Minister was occurring, you were one of the nominations, and this was the Chief Minister who would take to take Kiribati into independence. Can you tell me what it felt like when you were waiting for the decision about whether you – at age 29, I think – would or would not become Chief Minister?

IT: We five were all friends and we sat down and decided who should be leader. We knew we would become members of the new government, and that’s how we did it.

IJ: Were you willing or unwilling - did you have to be persuaded to become Chief Minister?

IT: When I first joined the government, I told my colleague from NZ (he now lives there permanently) that he should be our candidate for Chief Minister. He lost and over the next few years he deserted us and became the Minister of Finance with our opponents. So with our first preference gone and no-one else offering, I ended up as Chief Minister.

Being there at the right time is important in politics and I was there when the one we had wanted had gone, they looked around and that's how I came into the picture.

IJ: On the 12th of July in 1979, Princess Anne handed over the 'instruments of independence' to the people of Kiribati. What happened on that day?

IT: I can't remember much, but I know I was given some pieces of paper which had already been drafted and agreed. It was really a formality, to do with our constitution. I seem to remember the words 'Order-in-Council'.

The day was a big celebration. For me it was hectic. I had to look after so many VIPs and I was glad when it was over so we could spend more time on the real business of governing ourselves.

IJ: In your speech did you say anything that sticks in your mind?

IT: I can't remember what I said – it's a courtesy, that sort of thing. There's not much difference from country to country. They all say the same sort of thing. The real test is what happens afterwards.

IJ: Had you built your big maneaba – your parliament – by then? Is that where the celebrations were, the flags went up and down?

IT: No, it was all done on the small soccer field next to State House, that's where the celebrations were. There's no space on Bairiki.

IJ: How did the Princess manage in that heat?

IT: I'm sure they enjoyed it, except they were not used to such a small place as the Gilberts, but they were happy to see how the locals played their games and so on. After a day or two of that they went back home.

We are not used to fancy celebrations such as the Fijians have, you know, the kava drinking and the Police Band. I've seen some of them – and they can put on a show. But we are so tired out trying to find what to eat the next day!

IJ: You don't have an army at all, do you, did you have one then?

IT: When I came there was a Defence Force. I don't know where my predecessor got the idea from. We'd spent a lot of money on the Band and all the rest of it, but the first thing we did in government was to disband all of it.

IJ: Another thing you had to do was get the British to agree to top up your budget for 5 years because of the loss of the phosphate income. Was that easy to do ?

IT: Yes, we did that. We had plans and we put them there. Because of our determination to be rid of the financial aid we got, we gave up the aid ahead of schedule – because of my belief that political independence must be accompanied by economic independence as well. Even though we weren't economically independent, that was to show we were on our way towards doing things for ourselves.

IJ: So you had a five year arrangement, but you stepped away from it earlier?

IT: Yes.

IJ: I think, sir, that's the only country I've heard to do such a thing. And your people absolutely supported that ?

IT: I'm not sure – but on election day, I came back. We kept the main services going and the people were basically happy.

IJ: How did you decide how to use and develop your vast marine fishing resource? I know there was a problem with a deal you made with the Russians.

IT: We were the first South Pacific country to have a fishing plan. On the Russian thing – again, it's related to our strong view that it's better that we earn our own way. When the Russians were interested, I said "Yes, of course, if we can agree on the terms". That's how it all started. It was big news at that time.

I was abused locally, politically, by the church groups, with marches and so on, but I was convinced I was right. I did my homework, I studied the law and read about what had happened and I told them, talking to Australia and New Zealand "If you can license Russian fleets to catch your fish, why can't we?" And they really had no reason except " Well, you are too small..." and I came back and said "Under international rules, they can sail within 12 miles of our beaches without a fishing licence" and that's why I was convinced I was right.

I don't know, it may have changed the attitude of certain people. It's a funny world. Soon after that deal we made I went to Fiji and was surprised to be met at the airport by a senior minister of Ratu Mara's government. He took me to my hotel room and offered to do things for Kiribati – for the first time. So I said "No, I will not change." And that's the way it is.

IJ: You had an important effort to develop your own fishing industry through Te Mautari. How is that now?

IT: It's a long story. Early on we weren't able to make real progress. Nowadays – I'm no longer in government so don't know the details – but based on the information we've been given, the government is expecting some projects to be happening in the next few months. We now jointly own a purse seiner with our Japanese friends and there is a lot going on among PNA parties – countries working together with the tuna resource in this part of the world.

But as for Te Mautari after twenty years we still get only a 5 to 10 per cent return, which is too small.

IJ: When you went to be Secretary-General of the Forum, you'd be concerned not just about your country's fishing resource, but the whole ocean. I remember Ratu Mara despairing that we Pacific countries would never be able to control and develop our major resource.

IT: I used to share Ratu Mara's view but I hope that's changing, because if not our future is very bleak. I want to believe it's possible to earn a better income from the resource. According to the radio more than half the world's tuna comes from our part of the world, except we don't get a fair return on it. I hope the work done by the PNA countries will help us earn a far greater income. I heard they are reducing the fishing days by 30% - and they are meeting now in Hawaii. It's funny because all those countries that are fishing in our zone are our friends – South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, USA, but when it comes to economics, you don't have any friends – it's the money! That's the way the world is working; that's one thing I have learned.

We saw that with the phosphate when Britain, Australia and New Zealand sold it below the world price and when it came to residuals for us it was very low. Britain, Australia and New Zealand benefitted from the cheap phosphate.

IJ: After a wonderful career as Berititente of Kiribati and S-G of the Forum, there you are still as MP for Nonouti. What's the attraction?

IT: It's very simple. When I came back from Fiji, there's not much to engage myself in and my interest in politics is so strong. When you live on the atolls, you have to earn your living. It's very hard to find a job and without a job you're reduced to a very miserable existence. Politics is an area where I can make a contribution and it seemed obvious that I should re-enter it and represent my island. So I'm back.

IJ: What mark out of ten would you give Kiribati after more than 30 years of independence?

IT: I think we have earned a pass mark. There's still a lot of work to do. The problems here are immense. I may be old-fashioned but one thing holding us back a lot is fast population growth. It's affecting our standards, our environment, everything that we value. I continue to talk about this in the villages and in Parliament. Last week I told them the world's fertility rate – the number of children a woman will give birth to in her lifetime – in the developed countries, UK, France, Italy, Spain and all those, is over 1 per woman; in Kiribati it's in excess of 5 per woman. That we cannot afford. Unless we seriously address that, things will get worse.

IJ: What's the current population of Kiribati?

IT: We're having a census now, and I expect it may exceed 100,000.

Twenty years ago it was 72,000.

IJ: As you look at those Pacific countries which became independent thirty to forty years ago, where are they failing, where succeeding?

IT: That's hard. When I was at the Forum, it was my view that regional agencies can make a small contribution to development in the Pacific. The key to the development of each nation is at the door of national leaders. They have to take the hard decisions about moving forward. It's natural that the small islands states will continue to struggle.

I hope NZ's initative to expand the work scheme will go ahead. That's one thing that will have an impact on smaller countries.

Sir Ieremia Tabai