Ben Kingsbury

Photo: supplied

From 1906 to 1925 Quail Island in Lyttelton Harbour was the site of New Zealand’s only leprosy colony.

The fate of those who ended up on the Island was grim, with a lack of care and reports of institutional abuse.

While official record of the colony is light, historian and author Benjamin Kingsbury has pieced together the story through contemporary newspaper reporting and the letters of the people involved.

He's just about to release his book The Dark Island - Leprosy in New Zealand and the Quail Island Colony.

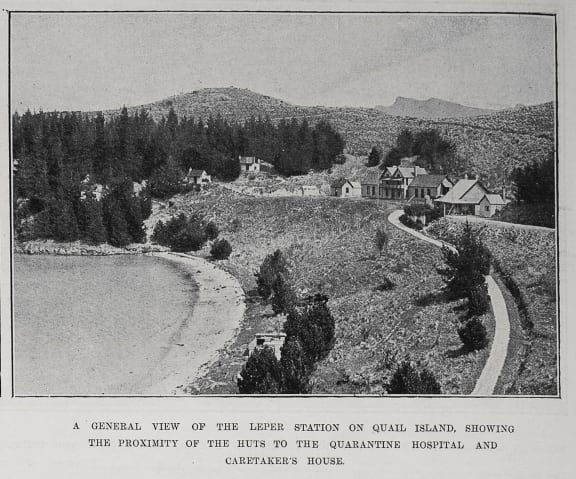

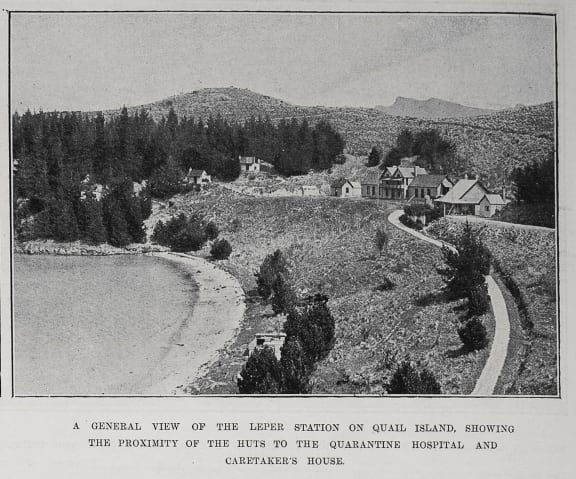

Views of the Quail Island colony in 1911. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19111026-16-2

The patients with Lyttelton Harbour in the background, early 1920s: from left, George Phillips, Ah Yip, Jim Lord, Ivon Skelton, Ah Pat and Pakira Matawai. Christchurch Anglican Diocesan Archives, Parish of Lyttelton Collection, PAR039

The patients on a hut verandah. The man standing in front of the railing on the left is most likely one of the Lyttelton residents who visited the patients to give them some company; the others, from left, are Ivon Skelton, Will Vallance, Ah Yip, Jim Lord, George Phillips, Ah Pat and one other, unidentified. Christchurch Anglican Diocesan Archives, Parish of Lyttelton Collection, PAR039

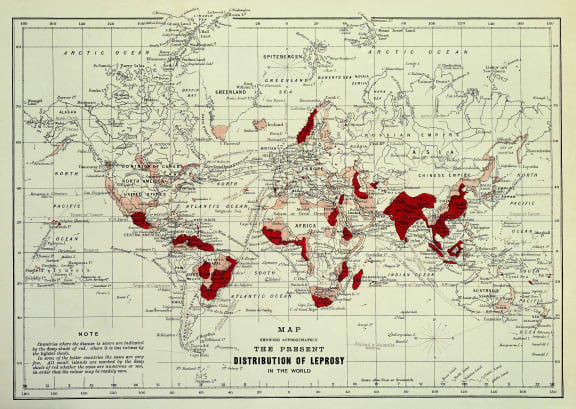

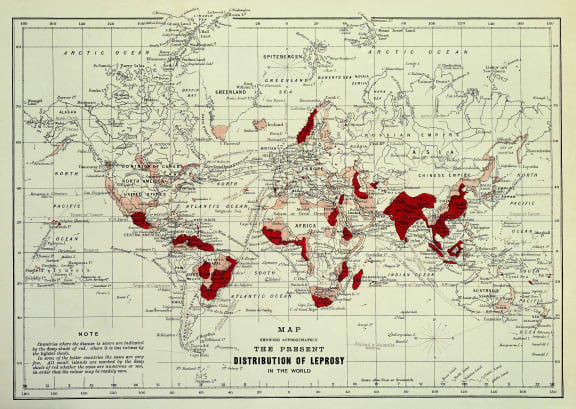

Part of an 1891 map showing the distribution of leprosy around the world. The disease was uncommon in New Zealand, but the lines showing the shipping routes from the Pacific, China and India suggest how easily it might spread. From George Thin, Leprosy, Percival and Co., London, 1891, Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0

Patients playing ‘clock golf’ in front of the unused recreation hall: from left, Will Vallance, Jim Kokiri, Ah Yip, Jim Lord, Ipirini Apa Apa and Ivon Skelton. Other pastimes included gardening, chopping wood, playing billiards and reading. Photograph c.1923, Lyttelton Museum

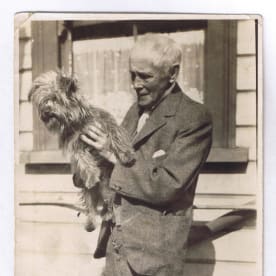

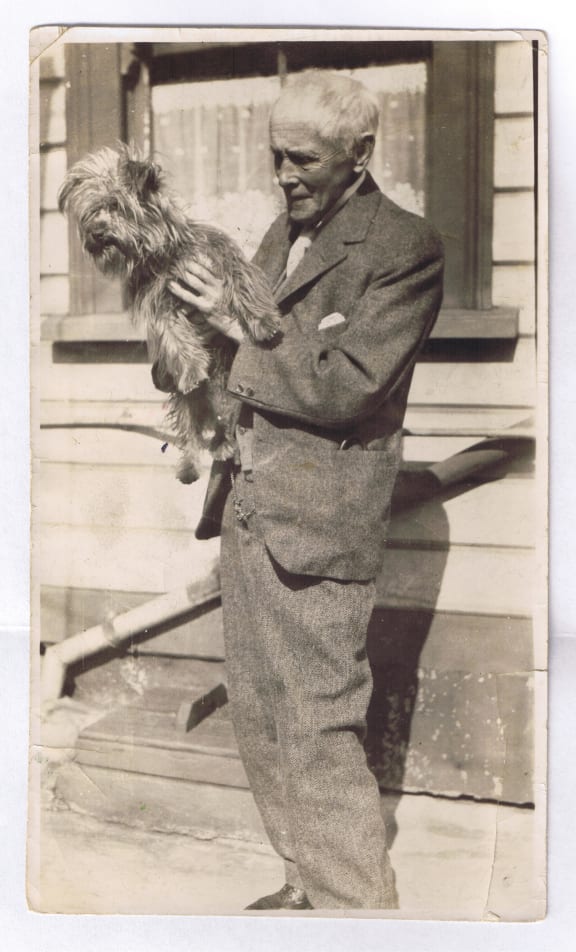

Charles Upham, ‘the little doctor’, with his dog Billie. Upham, who also had a general practice in Lyttelton, was the colony’s doctor for most of its nineteen years. During this time there was little progress in the treatment of leprosy, and as the number of patients increased Upham found it hard to keep up with the workload. The patients were grateful for his efforts, though, as well as for the moral support he provided. Lyttelton Museum, Nola Muir Collection, Z1132

The grave of Ivon Skelton. Skelton died on 20 October 1923, four years after he had been sent to Quail Island. His grave overlooks King Billy Island and the tidal channel on the western side of Quail Island – the path to freedom taken by George Phillips in 1925. Photograph by W.A. Taylor, Canterbury Museum, W.A. Taylor Collection, 1968.213.123