Our Changing World for Thursday 21 February 2013

Celebrating Wetlands

A fresh-water pond at the Tahuna Torea wetland.

Wetlands are often referred to as the kidney of the ecosystem, acting as a crucial buffer between the land and waterways. The Auckland Council’s biodiversity team has invited Aucklanders to discover the wetlands of their region this month, as part of a series of guided walks to mark World Wetland Day, which was on 2 February.

One walk was through Tahuna Torea, a 25-hectare nature reserve sited behind a long sand bank extending out from the suburb of Glendowie into the Tamaki Estuary. Translating as the 'gathering place of the oystercatcher', the mangrove lagoon, wetland and coast provide a sanctuary for a variety of birds including godwits, which gather between seasonal migrations back to the Northern Hemisphere.

However, the wetland does not exist today by chance. If city planners had had their way over 40 years ago, the wilderness of Tahuna Torea would have become a 'little Venice' or a residential marina. Met with opposition, that idea gave way to another solution for the overgrown wasteland as a rubbish tip, but a small group of dedicated local residents had other ideas and they've worked tirelessly to restore the site to its original condition.

Lisa Thompson was amongst a group of about 40 visitors who attended the council-hosted walk, led by local resident and Tahuna Torea advocate Chris Barfoot and the council's biodiversity advisor Michael Ngatai.

The next wetland walk will be taking place at 10am on Sunday, 24 February, at Harbourview-Orangihina Reserve (Te Atatu Peninsula).

Modelling Debris Flows

This simulation of a debris flow took a week to set up and eight seconds to run. It shows a normal debris flow, where large 'boulders' travel in front and spread out across the level fan at the end of the slope, while smaller 'rocks' spread out up the slope (image: A. Ballance)

Elisabeth Bowman (below left) is a geotechnical engineer in Civil and Natural Resources Engineering at the University of Canterbury. She is interested in understanding land movements, and how sand and mud move and behave under different conditions, depending on the slope and degree of saturation.

She is particularly interested in debris flows, which are a highly unpredictable hazard in areas of mountainous terrain and high runoff. They are one of the most frequent mass movement processes, made up of high-speed gravity-driven mixtures of soil, rock, and water moving down a channel such as a gully. Mechanically, debris flows are particularly complex because they have a large range of clast sizes, from boulders through to silt. The most famous debris flow in New Zealand happened at Matata (PDF) near Whakatane in 2005, following very intense heavy rainfall, causing more than $10 million dollars worth of damage to houses and roads.

She is particularly interested in debris flows, which are a highly unpredictable hazard in areas of mountainous terrain and high runoff. They are one of the most frequent mass movement processes, made up of high-speed gravity-driven mixtures of soil, rock, and water moving down a channel such as a gully. Mechanically, debris flows are particularly complex because they have a large range of clast sizes, from boulders through to silt. The most famous debris flow in New Zealand happened at Matata (PDF) near Whakatane in 2005, following very intense heavy rainfall, causing more than $10 million dollars worth of damage to houses and roads.

To help understand what is happening during a debris flow Master's student Josh Bird has been modelling them in the lab using different sized glass pebbles in a thick oily liquid. He films the model flow with a high-speed camera and laser so he can analyse the behaviour of the flow. Alison Ballance meets Elisabeth and Josh to observe one of these mini debris flows in action, which take one week to set up and run, and last just eight seconds. This research project is part of a Marsden grant called 'Investigation of the internal mechanics of debris flows’.

Chemical Fingerprinting of Old Photographs

Dusan Stulik is analysing the chemical composition on a photograph using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (image: Art Kaplan, Getty Conservation Institute)

Silver, gold and platinum are among the better known materials used in tranditional photography, but a research project led by the Getty Conservation Institute has identified more than 150 different chemical processes which rely on an array of materials, including bitumen, egg white, gun cotton and even uranium.

Dusan Stulik, who manages the project, has made it his job to catalogue the various chemical processes that have been employed to make and fix images since 1826, when an amateur scientist by the name of Joseph Nicephore Niepce made what is thought to be the first permanent photograph. Niepce used a pewter plate, which he coated with bitumen mixed with lavender oil.

In this interview, Dusan Stulik explains the techniques he uses to identify chemical elements in old and often precious photographs, ranging from microscopy to detailed chemical methods such as X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, or XRF. The latter technique can determine the chemical composition as well as the concentrations of various materials in a photograph without touching the image (as shown in image above).

Dusan was in New Zealand last week to discuss the project and to advise conservators during a joint meeting of the American Institute for Conservation and the International Council of Museums, hosted by the National Library of New Zealand and Te Papa Tongarewa.

Forensic Laboratory Tour - Part Two

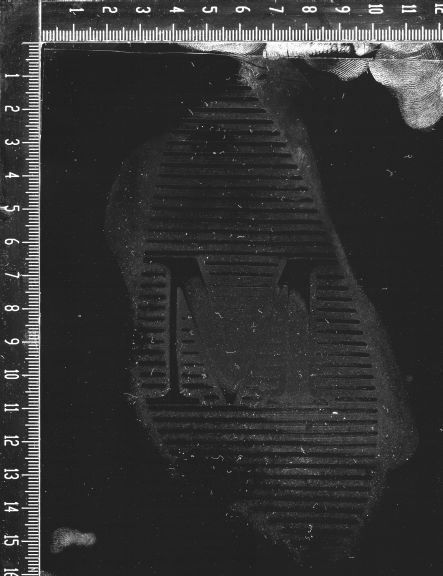

Shoeprint captured with a gel lift and scanned with GLScan

Following on from last week, Ruth Beran continues her tour with Steve of the Wellington Forensic Service Centre at Environmental Science and Research. First she meets Mark, who is testing a gel scanner for footwear impressions, as part of the Future Crime Scene Project.

The shoeprint is made using Vaseline, which is then dusted with white fingerprint powder which attaches to the detail in the print. A gel lifter - a black, sticky gel substance - collects the shoeprint and picks up the contrast between the white and black. The shoeprint can then be stored on the gel lifter for a long period of time.

At the moment, Mark is testing different fingerprint powders to see which one works the best. Traditionally, the shoe print is photographed using oblique lighting which shines on the shoeprint at a certain angle. However, Mark is trialling GLScan, a  scanner which scans the gel lift at a high resolution, allowing fine detail of the shoeprints to be picked up. Prints from the bottom of the shoe and a print at the crime scene can then be checked for comparative damage from wear to see if they match.

scanner which scans the gel lift at a high resolution, allowing fine detail of the shoeprints to be picked up. Prints from the bottom of the shoe and a print at the crime scene can then be checked for comparative damage from wear to see if they match.

Ruth then meets Glenys who checks samples when there has been an allegation of sexual assault. The most common sample is a medical examination kit which is taken from the female complainant by a doctor. Slides made from swabs are stained and checked for sperm, which are a good source of DNA. Sperm in the vagina lose their tails at a pretty standard rate so the sperm are also evaluated to determine how many still have tails on them. This can give some idea of when sex last occurred, prior to the medical.

Difference between shoeprint captured using GLScan (left) and traditional methods (right)