Anybody in need of joint replacement surgery will appreciate the options modern medicine provides, but if Kate McGrath has her way, future patients won’t require any screws or other metal parts in their new hips or knees.

Researcher Natasha Evans, left, and MacDiarmid Institute director Kate McGrath with a 3D-printed cylinder of their material. (image: V Meduna)

The director of the MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology and her research team are borrowing ideas from nature to develop implant technologies based on biominerals, natural materials built through molecular self-assembly.

Most joint implants used today are made of ceramics of metal alloys, which are durable and strong. “But bone is a bit like chalk,” Kate says. “Imagine a bit of chalk and a metal coin that rub against each other. Which is going to wear out first?”

Biominerals are everywhere, from the patterned walls enclosing microscopic algae to the massive bones of a whale. Our bones and teeth, and even the tiny otolith in our inner ear, are also biominerals, as are kidney and gall bladder stones.

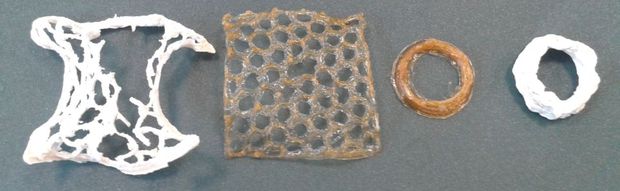

Natural biominerals are often elaborate in detail but light, durable and strong. They are usually able to regenerate when damaged. Researcher Natasha Evans says the team mimics the biomineralisation process, and with the help of 3D-printing, it is now possible to begin recreating the natural structure of bone.

Mechanicals tests have confirmed the strength of the material, and biological tests have shown that bone cells tolerate it well. These results are doubly promising. Such materials could not only improve the durability of implants, but also help damaged bone to heal itself.

You may also be interested in our earlier story about a trial to test a new form of highly cross-linked polyethylene used in the lining of hip implants.