"Sunday 25th April 1915, Gallipoli

Came ashore in destroyer Beagle . Wounded everywhere. Sights appalling. I did what I could. It seemed so little. Poor fellow with eyes protruding. Another with bullet in throat. Men bleeding to death. Oh, what sights”.

– From the Dairy of the Reverend John Aldred Luxford, Methodist Chaplain NZEF

Diary and photo of John Luxford supplied by Bob Luxford.

An historian who’s studying the role of the churches in the First World War says they developed a ‘war rhetoric’ in an attempt to make sense of the carnage. Dr Allan Davidson is Honorary Research Fellow at both St John’s Theological College and the University of Auckland.

Allan is studying the work of some of the almost 140 chaplains who served overseas in World War One alongside the troops, and plans to write a book about them.

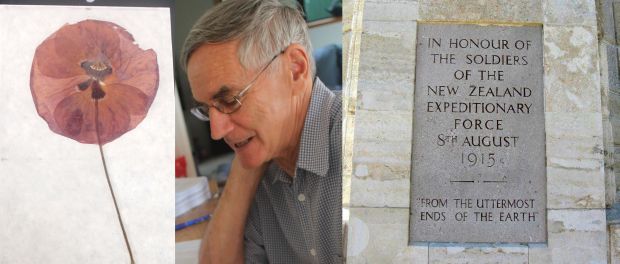

Left: Poppy preserved from Gallipoli, Middle: Dr Allan Davidson. Photos: RNZ David Steemson. Right: Inscription on New Zealand Memorial at Gallipoli. Photo: Margaret Davidson.

He’s had career-long interest in the history of Christianity and its impact on New Zealand Society. He’s also been studying religion and the First World War, and the role played by the chaplains, who, as army officers, were sent to the war fronts. Their job was to conduct Christian services and to bury the dead. But as part of their pastoral duties they also had to boost the morale of the living.

Reference books

Writing in an article “Centenary Reflections on Gallipoli” published in this month’s Tui Motu Interislands Catholic magazine, Dr Davidson says; ”the narrative of Gallipoli is woven into New Zealand’s national mythology. From the very beginning it was embroidered by war rhetoric which mixed duty to God, King and Country with the language of sacrifice, honour, courage, bravery, patriotism and heroism”.

He says the churches themselves deified duty. They saw the war as a good cause, and some ministers even thought of themselves as recruiting sergeants operating from the pulpit. He thinks the churches hoped the war would bring about their revival. But it actually turned some soldiers off institutionalised religion.

He says the churches themselves deified duty. They saw the war as a good cause, and some ministers even thought of themselves as recruiting sergeants operating from the pulpit. He thinks the churches hoped the war would bring about their revival. But it actually turned some soldiers off institutionalised religion.

60-year-old Methodist, the Reverend John Luxford, was one of six Chaplains who landed at Gallipoli with the New Zealand troops on the 25th April 1915. Three days earlier in his diary he’d written, “I shall be glad to get to the real work”. But when he got there, he was appalled.

"Sunday April 25, 1915

Poor Col. Stuart is dead. We have lost heavily. I must leave the scenes for future description. Saw several dead. Many wounded and left, and dead are not yet brought in. Shrapnel bursting all around us, men hit within three yards of me. The Turks were on the shore when the Australians landed. They misled our troops by running away thereby drawing on our men who were caught by superior numbers. We had no Artillery with which to cover our men and no reinforcements to help them.

“Monday April 26, 1915

I am tired today. Could not get a good night’s sleep. Helped our wounded this morning. With Father McMenamin, I buried nine poor fellows. We had to shelter for an hour. The guns were booming. Then as we read the service we had to kneel down in the dug grave. It was terrible. Six were buried in one grave and three in another. Buried nine more men… four from boats where they had been killed in trying to land under fire.”

– From John Luxford’s diary.

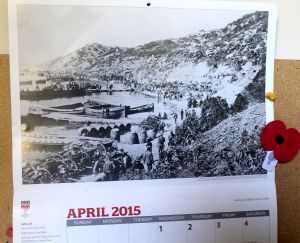

Anzac Cove beach, photo: Margaret Davidson

Allan Davidson says chaplains at Gallipoli suffered from the fighting along with the soldiers. Presbyterian William Grant was killed; Father Patrick Dore was shot in the spine at Gallipoli and died on the operating table back in New Zealand in 1918. Father Joseph McMenamin had to be evacuated ill and was later killed in France while conducting a funeral. On the 8th August 1915 at Chunuk Bair, John Luxford was shot in the leg, which had to be amputated. At that point his diary ends.

Again in his Gallipoli Centenary Reflections, Davidson says “for a chaplain, dealing with the overwhelming pastoral demands, brought on by what Luxford called an ‘Inferno’, was all consuming. For the generals and politicians it was hard to admit that they had made strategic blunders and launched their men into a futile campaign”.

Again in his Gallipoli Centenary Reflections, Davidson says “for a chaplain, dealing with the overwhelming pastoral demands, brought on by what Luxford called an ‘Inferno’, was all consuming. For the generals and politicians it was hard to admit that they had made strategic blunders and launched their men into a futile campaign”.

He says soldiers came back to New Zealand after having seen the terrible reality of war. Many came with injuries themselves, and found a society where the war mythology was already in place. It was hard for them to speak of what they had been through.

The Reverend John Luxford spent the remainder of the First World War as the senior Methodist chaplain at “New Zealand General Hospital Number Two” at Walton of Thames in England, where according to one writer he was held in awe by those who’d not been to Gallipoli. Luxford returned to New Zealand in 1919 but died from the effects of his service in 1921.

Photo: John Luxford's grave at Waikaraka Cemetery, Onehunga