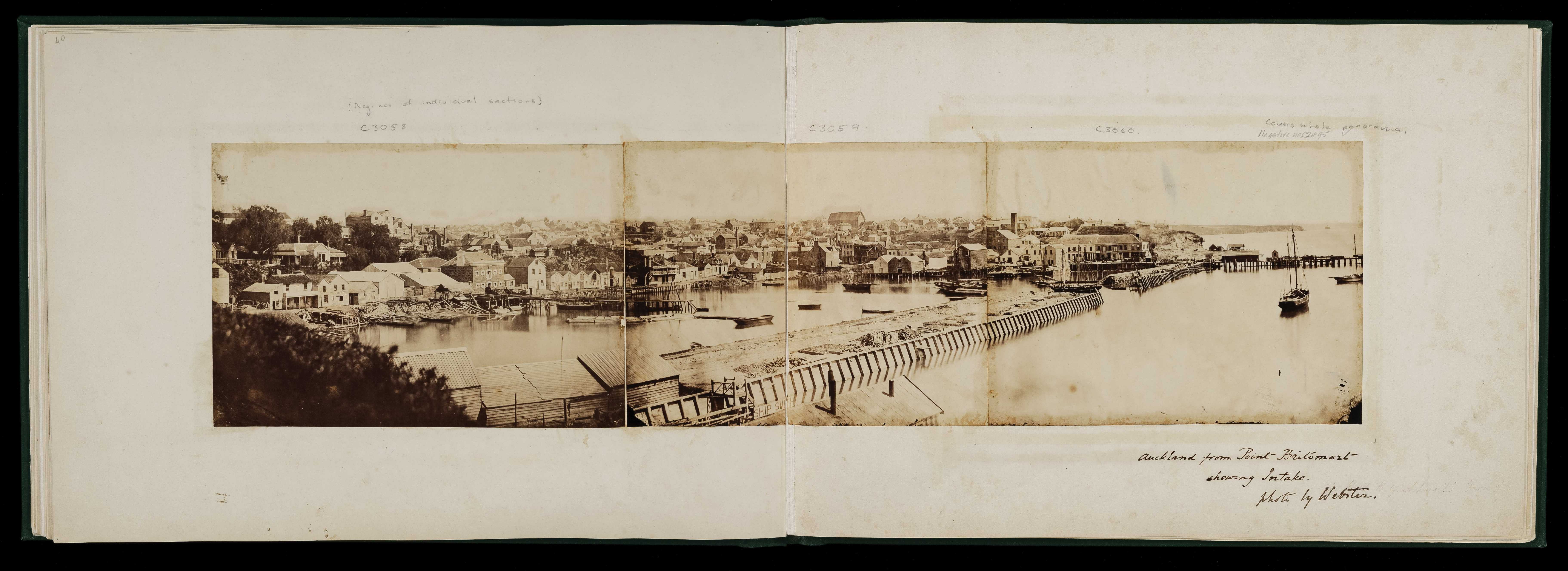

Women had to disguise themselves in 1800s photographs of their babies due to early cameras' long exposure times. Photo: Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum.

It was the mid-1800s, and New Zealand mothers faced a dilemma.

Photography was sweeping the nation, and they wanted a likeness of their babies - but could not leave them sitting alone while the image was captured, which could take up to 45 seconds.

Enter a phenomenon that book editor Shaun Higgins calls the 'hidden mother': women preserved in early photos crouching behind chairs, or hidden under a shroud of fabric, propping up their young children.

In some photos, their disembodied hands could be seen emerging from a cloth, holding their babies tight "lest they topple over".

An example of the 'hidden mother' is displayed on the front cover of Higgins' latest book, A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa.

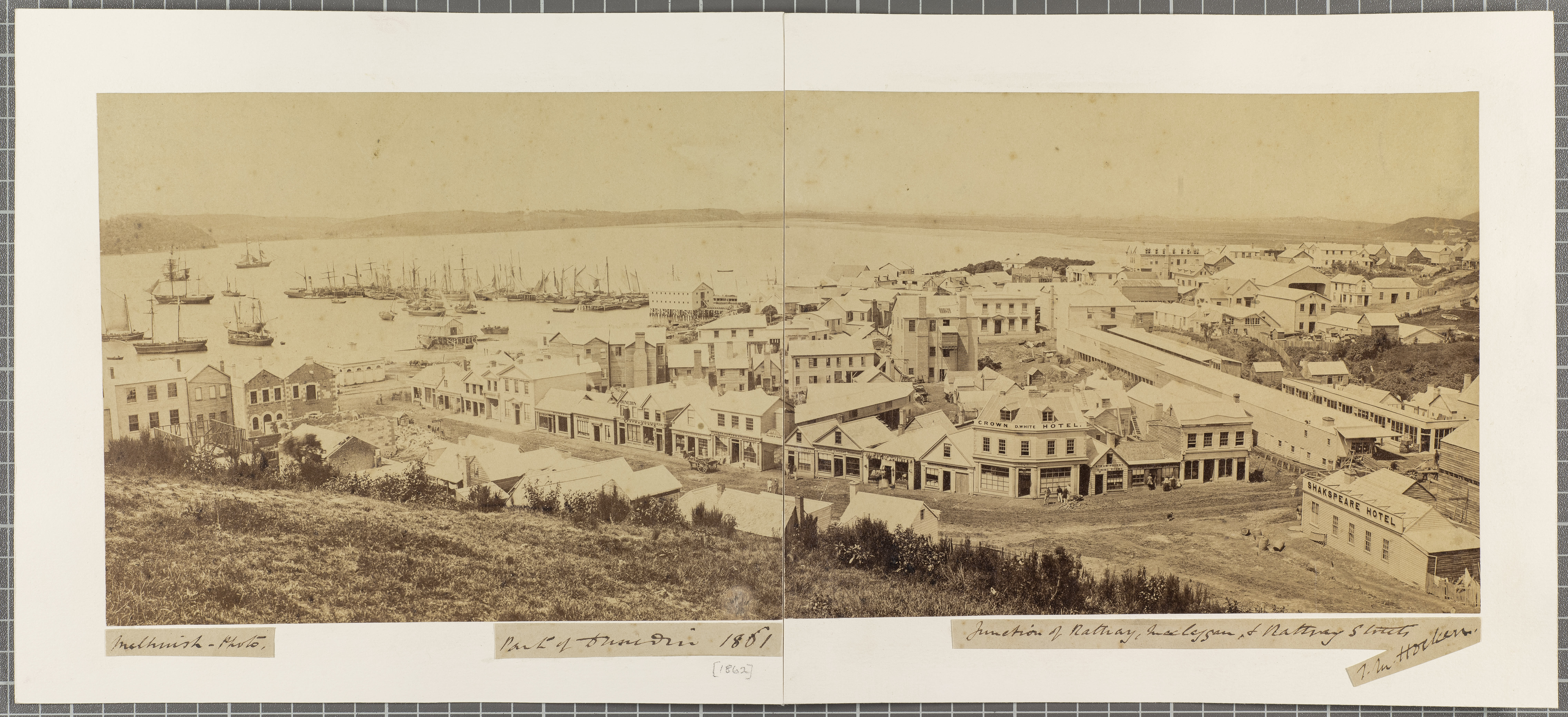

Along with fellow editor Catherine Hammond, he pulled from the extensive photo collections of three major research libraries: Auckland Museum, Hocken Collections, and the Alexander Turnbull Library.

The resulting tome includes an array of portraits and landscapes, providing an insight to New Zealand's colonial era.

Higgins told Saturday Morning that photography was introduced in Aotearoa in 1848, about a century after its invention in France.

The book's co-editor Shaun Higgins. Photo: Supplied

The earliest surviving photo taken in Aotearoa was a portrait of a "rather bewildered man" named Edward Catchpool, who sat for a portrait in Wellington in April 1852.

"He actually looks like a confused first-time Tinder user. It's quite a funny portrait, but you have to put yourself in his shoes and remember that he's never seen a camera before," Higgins said.

Many people looked at early photographs and thought "gosh, it must have been pretty miserable back then", he said - but their serious expressions were usually because they had to sit still for a long time.

"Dentistry was [also] not very good back then, so they don't tend to want to do a big grin and show their mouth."

The earliest surviving photograph taken in Aotearoa was this portrait of Edward Catchpool, taken in 1852. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library, Margaret Dunne collection.

Early photographers had to cart a cumbersome kit around New Zealand, Higgins said.

As well as their cameras and tripods, they had portable darkrooms - usually a small tent or a covered cart - because negatives had to be processed straight away.

One image included in the book, of the Pink and White Terraces, had been captured on a 50cm plate, he said.

"You think about a piece of glass that size being taken to the Pink and White Terraces, that's when your imagination starts to go wild."

An image of the Pink and White Terraces before they were lost in the 1886 Mt Tarawera eruption. Photo: Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Museum

The camera's body would have been at least as big as the plate, then there were the bellows and lens on top.

Higgins referred to it as the "giant megapixel camera of the time".

The image would have been processed in a small tent nearby, "then they would have washed the plates in the waters of the terraces".

Portraits of Māori were popular in those days, but many photographers exploited them for profit, Higgins said.

Kīngi Tāwhiao used photography to "spread his image around Aotearoa and the world". Photo: Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum.

The idea was that "Māori were a collectible", and photographs the size of business cards, called carte de visite, were taken of anonymous sitters and mass produced.

Higgins said the sitters did not receive any payment for posing for the images, which became sought-after and frequently swapped, like trading cards.

Their portrayal could be contrasted with that of Kīngi Tāwhiao, who sought out portrait photographers and "embraced this technology as a way to spread his image around Aotearoa and the world", he said.

"Instead of being for the benefit of Māori, this is actually the complete opposite - this is predominantly for a Pākehā collector audience."