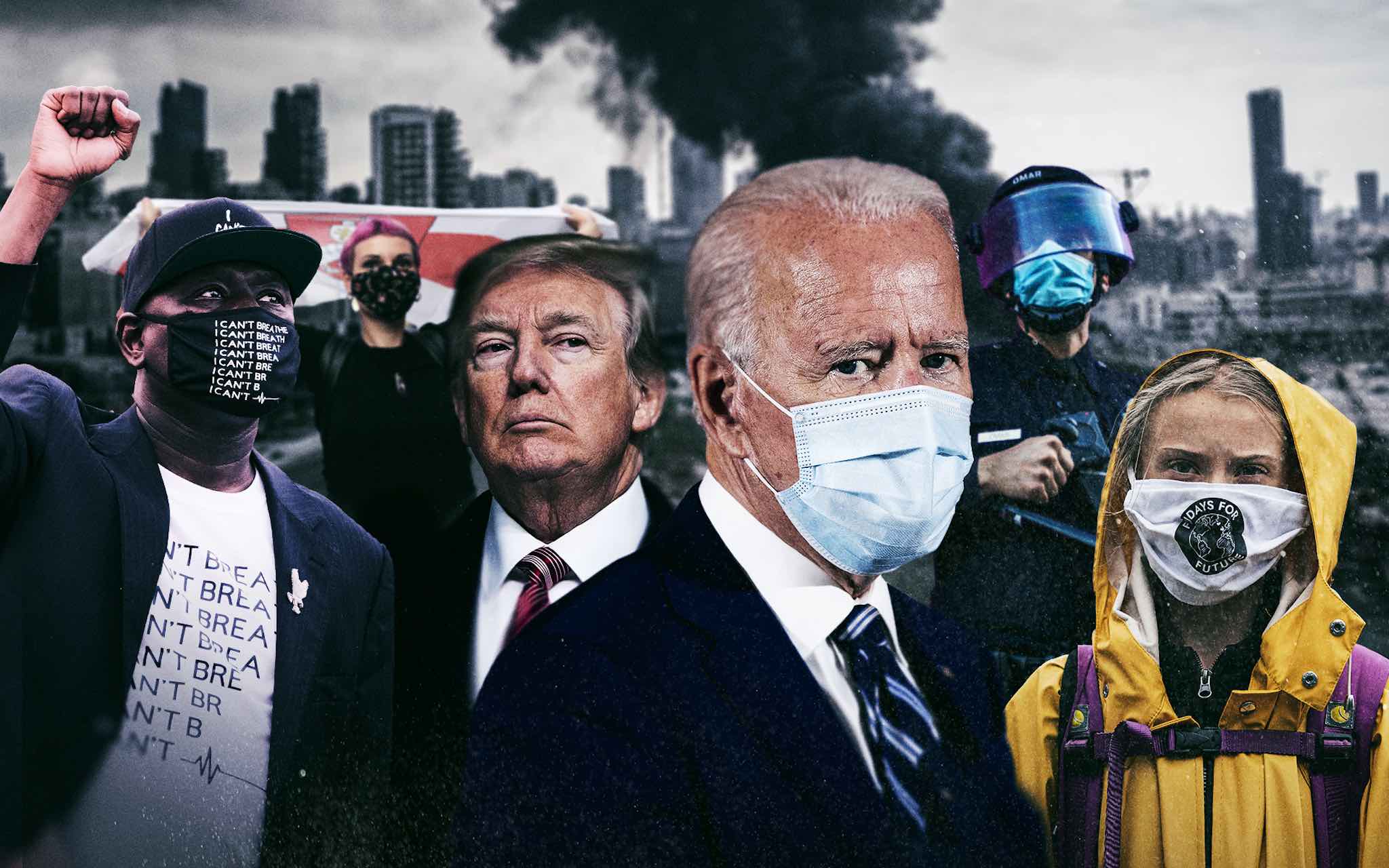

The stories that made international news in 2020

Every year, it seems, we exhale at the end of December and moan about how bad our collective years have been.

Every year, it seems, we exhale at the end of December and moan about how bad our collective years have been.

But 2020 hit different.

The most significant story of the year was the most significant in recent memory — the pandemic — or “Covid,” or “Corona,” or however you might describe an event which dominated, and forever changed our lives.

Think back to January and February — a simpler time.

Back then there were warnings about the infectiousness of a new type of virus discovered in Wuhan, China.

On January 23, the city went into lockdown and most of us barely batted an eyelid.

The number of cases doubled roughly every week during the early days of the outbreak.

China — a country with a population close to 1.4 billion — would report new daily cases in the hundreds.

By the end of January, there were about 8000 confirmed global infections.

Still — not enough to deeply trouble health officials in most countries.

News media were criticised for either giving too much attention to the coronavirus, or not enough.

By mid-March, Europe — and specifically Italy — was considered the centre of the pandemic.

Towards the end of March, the United States had reported the most cases.

By that point, there were about 50,000 confirmed cases being recorded every day, and more than 1.7 billion people worldwide were under some form of lockdown.

The worst day since then has been November 28, when close to 800,000 global cases were recorded.

It’s difficult to sum up the impact of the pandemic in a few words, but it has forever altered the world.

The coronavirus has decimated economies — sparking the largest global recession since the Great Depression — and devastated industries.

It has ingrained terms into the global lexicon — terms like “lockdown,” “social distancing,” and “contact tracing.”

It has also driven people apart.

Hoards of people in dozens of countries have vented their rage via anti-lockdown protests, carrying signs that preach freedom and bemoan government control.

Conspiracy theories about the seriousness of the coronavirus, and the purpose and effectiveness of vaccines, have also been rampant.

It’s understandable that such an unprecedented era as this should spark fear and uncertainty — and nothing stokes the spread of hoaxes like fear and uncertainty.

But overall, people have grasped the importance of restrictions.

Much of the Australian state of Victoria, for example, raged at premier Daniel Andrews for enforcing a near four-month lockdown after an outbreak, yet coming out the other side, his approval rating soared from 12 percent to 71 percent, according to Roy Morgan polls.

America may be harder to convince, but people do get it.

It’s probable the pandemic — or rather his handling of the pandemic — cost Donald Trump the US presidency.

The White House’s lack of a coordinated plan to tackle the spread of the coronavirus turned many Americans away from the president.

Early on, he told the country that he would defeat the virus.

When it soon became apparent that he wouldn’t, the president shifted the blame to state governors.

Since Joe Biden’s victory early in November, President Trump has barely mentioned the pandemic, despite the staggering late-2020 numbers in the US.

There have been record hospitalisations, record fatalities, and daily cases regularly beyond 200,000.

The problem Joe Biden faces in 2021 is convincing a country riddled with an anti-science bias and a misguided obsession with ideals of freedom to observe new restrictions — or at least enough people to make a difference.

The president-elect has promised a nationwide mask mandate but enforcing it will be difficult.

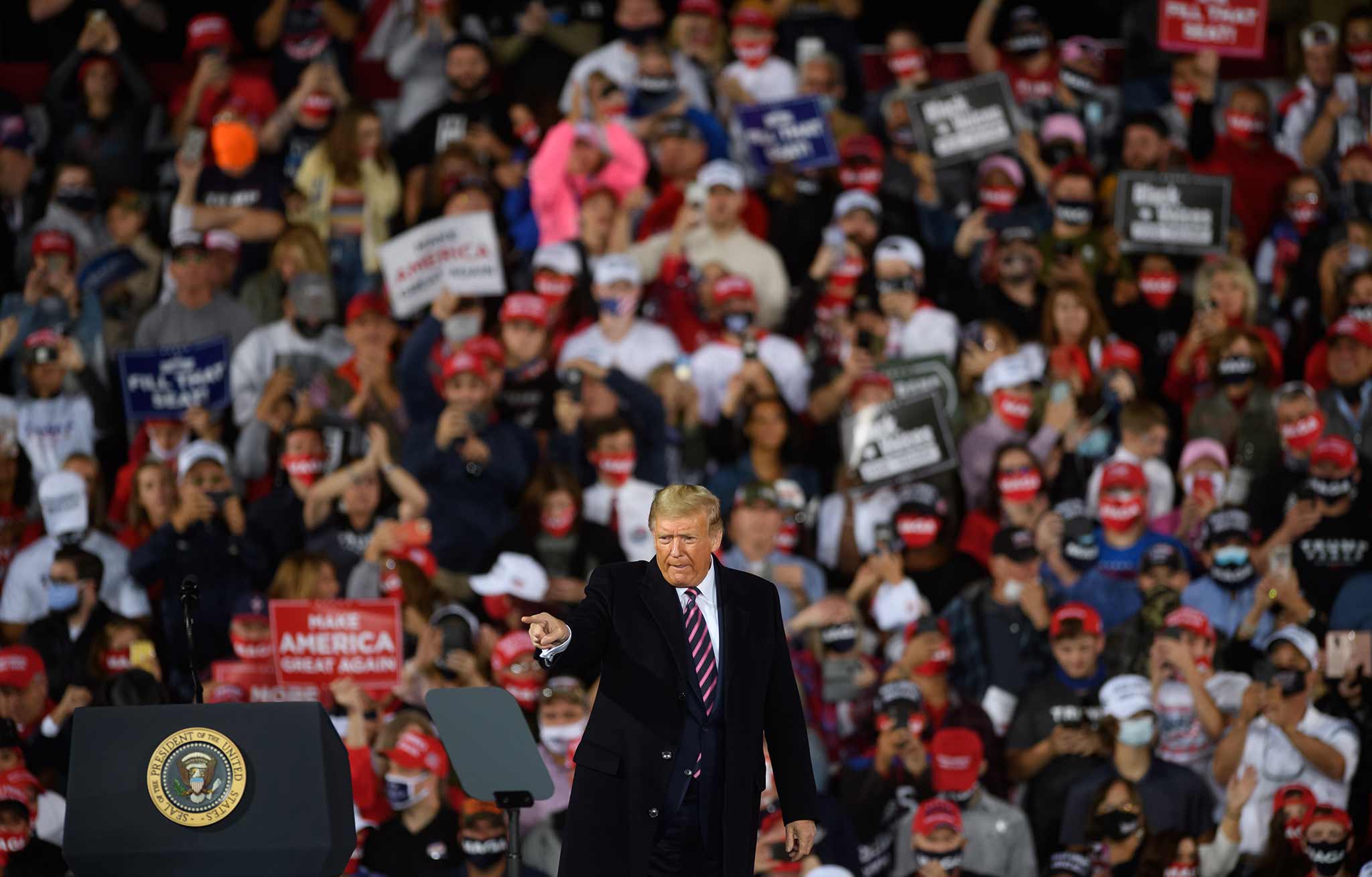

As for the election itself, the campaign was particularly bitter and further split a country torn into shades of blue and red.

And in terms of its security, Donald Trump had begun planting doubt in people’s minds well before November 3.

In fact, for four years he has seeded the idea that the election would be rigged.

He has destroyed faith in the integrity of the vote — and in democracy itself — and it may take generations to recover.

It is not enough for the media, for courts, for the president’s own officials to debunk his claims — he has become a cult leader with an obedient support base that won’t soon dissipate.

He may run again in 2024, he may start his own television network.

What is certain is that he leaves behind a country divided.

At no time were those divisions more evident that following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May.

The Black Lives Matter movement was not about looting or destruction — as the president sought to depict — but fighting against racial inequality and police brutality.

In the weeks that followed officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes, mass demonstrations took place in more than 60 countries across seven continents.

Yet Donald Trump wrapped the misbehaviour of a minority into his tough-on-crime narrative.

One of the most memorable sights of 2020 was the police brutally pushing back peaceful protestors from the White House, allowing Donald Trump to pose for photos at a nearby church while emptily brandishing a bible.

In 2011, Time Magazine unveiled its Person of the Year as “The Protestor.”

The same could, and should be said, for 2020.

There were protests in every corner of the world — people standing up for, or against, issues they cared deeply about.

In Belarus, for instance, hundreds of thousands have taken to the streets, week after week, to protest the disputed re-election of the country’s authoritarian leader Alexander Lukashenko, who won with an inconceivable 80 percent of the vote.

Alexander Lukashenko’s iron grip on Belarus may remain, and the repression of pro-democracy activists may continue, but the country’s people no longer bow to political oppression.

Pro-democracy is also a term frequently used in referral to activism in Hong Kong.

A national security law that came into effect in June further eroded freedoms, and tightened China’s grip over the supposedly-autonomous city.

The growth of a protest movement, led by younger people, has led to violent clashes with police, and the detention of thousands, including pro-democracy politicians.

Protests — and strikes — against political inaction on climate change also won’t soon die.

United alongside the Swedish activist Greta Thunberg, young people in thousands of locations around the world in September chanted for their futures.

We were shocked in early August by the amateur videos capturing the explosion that destroyed most of Beirut.

The blast — sparked at the port in a warehouse containing large quantities of ammonium nitrate — killed more than 200 and injured about 6500, and caused damage estimated at about $21 billion.

It also exposed a country rife with corruption — following August 4, protests erupted across Lebanon against a government many blamed for not having done more.

As there are every year, there were also impactful celebrity deaths in 2020.

The basketball legend Kobe Bryant died in a helicopter crash, the actor and star of Black Panther, Chadwick Boseman, succumbed to his secret battle with colon cancer, the definitive James Bond — Sean Connery, died at 90, the Argentinian footballer Diego Maradona passed away, while the Glee actress Naya Rivera drowned in July.

Some deaths forced us to grapple with the difficult legacies some of these heroes leave behind.

Kobe Bryant, for instance, was an immensely positive influence, particularly — late on in his career — in women’s basketball.

Yet we have to also be honest about his life — and reckon with the criminal case brought against him in 2003 regarding allegations he sexually assaulted a 19-year-old.

The case was dismissed, yet Bryant would apologise and admit the woman had not consented.

Sean Connery, too, has in the past made terrible comments regarding violence towards women.

It’s also worth mentioning that in February, the disgraced movie producer Harvey Weinstein was sentenced to 23 years in prison after being found guilty of rape and other sexual abuses.

The #MeToo movement is two years strong, and workplaces around the world have slowly adopted changes in response to stories of abuse from women of all backgrounds.

There are new standards, but we are not there yet.

About the author

Max Towle is RNZ’s Worldwatch reporter.