'Help is on the way' – pamphlets distributed after Allies liberated Singapore in 1945

Weeds can’t be killed, they can survive anything! - Jean de Bruyne, daughter of Roland de Bruyne, Changi/Sime Road Internment Camp Survivor.

Gallery: Changi Prison survivor

The dining table is littered with Roland de Bruyne's memorabilia. The objects are imbued with grave meaning; faded love letters to his sweetheart Low Swan Tin on crumpled Australian Red Cross paper, albums of sepia photographs, British Army pamphlets, a fragment of rusted bomber shrapnel wrapped in tissue.

When Singapore fell to the Japanese on 15 February 1942, the British had prayed that relief forces might arrive, but it wasn’t meant to be.

During the Fall of Singapore that year the Imperial Japanese Army detained around 3000 civilians in Changi Prison, built to house only 600. The British Army Barracks nearby became a prisoner of war camp, housing around 50,000 allied British and Australian troops. Changi Prison and the nearby Prisoner of War (POW) camp were rife with sickness and death. 73 years later and a world away in Auckland, one survivor tells me his story.

Roland de Bruyne is Eurasian, 91 years old this year, born in 1924 in Penang, Malaysia. He was imprisoned by the Japanese Military, along with his entire family and 3000 other civilians in Changi/Sime Road Internment Camp in Singapore during the Second World War simply because they were Eurasian.

Roland de Bruyne is Eurasian, 91 years old this year, born in 1924 in Penang, Malaysia. He was imprisoned by the Japanese Military, along with his entire family and 3000 other civilians in Changi/Sime Road Internment Camp in Singapore during the Second World War simply because they were Eurasian.

Image: Roland de Bruyne and daughter Jean de Bruyne

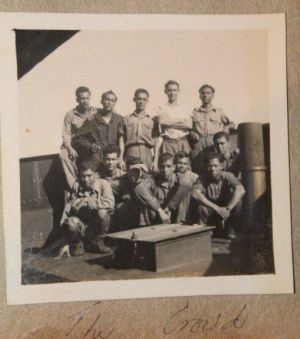

They were stripped of clothing and belongings, starved and forced into hard labor. The tiny black and white photos that Roland shows me were taken by him on a camera smuggled into the prison. In one photo, almost naked, Roland's friend is a skeletal figure in a loin-cloth. This was all the clothing they were allowed.

Miraculously Roland's whole family, all except one, survived. Roland's little brother Jimmy died from dysentery at the age of five during the war. Jean notes that perhaps a small mercy that little Jimmy died before the family were interned in Changi. "It's one of the ravages of war."

Roland's daughter Jean de Bruyne states proudly that “You can’t kill weeds.” Jean tells me her father is remarkably healthy for a 91 year old, let alone a survivor of Changi. If the prison ordeal couldn't kill him then almost nothing would. The tenacity to live runs strong within the de Bruyne family.

Jean's home in Greenhithe, Auckland is a serene retreat; surrounded by lush bush and peaceful, just the kind of home a survivor of 91 needs to quietly reside in. As Roland talks Jean sits close by, helping her father remember which story to explore. He has a lifetime of memories to share. Roland begins by explaining his Eurasian/Malaysian ethnic heritage. He's a product of British and Dutch colonisation of the East:

“Both my grandparents were Eurasian; both first generation born in Penang in the late 1800’s. My father was the son of a Dutchman who married a Burmese woman. My mother was the product of Scottish Engineer, James Irving (my grandfather) who married a Malay woman.” Roland family are now four generations of Eurasians, counting daughter Jean and her children.

Roland is an “old-free”. He attended Penang Free School in George Town, Penang, a British government secondary school first established in 1816, almost 200 years ago. Roland grew up during the last era of British Imperialism.

Roland remembers most vividly his friends at school, Sikh boys, the sons of officers with the British Army. The Sikh boys all hoped to gain scholarships to attend the Royal Military Academy of Sandhurst.

Penang Free School was also attended by many Japanese children, ironically some parents turned out to be secret service spies for the Japanese Military.

Roland vividly recalls around 1936, the first time he had tried sushi and learned to bow. He was taught by his Japanese classmates during their farewell, they were returning to their motherland with their parents. It was a national call to service by the Imperial Japanese Army.

One of his Japanese school friend's enlisted and died as a Kamikaze. All the Sikh classmates except one lost their lives fighting the Japanese. After the war, the sole surviving Sikh friend came back home to kiss the floor, thanking God for his life.

Low Swan Tin was Roland's childhood sweetheart. Their families lived next door to each other in Penang. Swan Tin was almost the same age as Roland. they played together every day. They were destined to be together even though Low's "true-blue" Chinese family strongly disapproved of her marriage to a young "half-caste" Eurasian man.

Roland graduated from college and trained as a ships engineer with the Straits Steam Ship Company, a shipping firm that operated cargo and passenger boats around Southeast Asia; India, Hong Kong. He was 19 and serving long months at sea on cargo and passenger ships. While at sea Roland wrote to his sweetheart all the time, they would see each other whenever he was in port.

Roland graduated from college and trained as a ships engineer with the Straits Steam Ship Company, a shipping firm that operated cargo and passenger boats around Southeast Asia; India, Hong Kong. He was 19 and serving long months at sea on cargo and passenger ships. While at sea Roland wrote to his sweetheart all the time, they would see each other whenever he was in port.

When Roland returned to Singapore the Japanese had invaded. Singapore was renamed Syonan-to (Light of the South). Roland and his family were interned in Changi alongside thousands of others. Jean reads out his internment camp registration card: "Sime Road Internment Camp: Name: R.I. de Bruyne, Hut: 130, Relationship: Son."

Swan Tin's Chinese family stayed on in Penang and escaped internment but they too endured the Japanese occupation.

One hundred grams of rice per day, that was our food ration. We were lucky if we got some vegetables.

The Japanese Military were notorious for starving inmates. Worse still was the death railway, the 415km of railway that the Japanese Empire began building in 1943 to connect Burma and Thailand during their Burma Campaign.

If starvation and sickness didn't kill you then the 'death railway' would.

Many POWs from Changi were sent to work there. Roland says that for every railway sleeper, there was one death. Over 100,000 Allied POWs lost their lives to this railway.

I ask Roland about the cruelty of the Japanese Military during his internment: "Cruelty was like this: starvation, no clothes, bore-holes in the ground for latrines. There were about 1000 fellas, all of us crowded together in one hut."

As a young and fit man Roland was sent to work reconstituting railway sleepers for the 'death railway'. He worked in chain-gangs, digging up sleepers and granite to be sent on to Thailand to fortify the railway. Those in his group that fell sick to dysentery, malaria or cholera were left to die. "There was a separate shack for sick fellas. Six burials a day, they buried six people a day, just from my section of camp in Changi/Simes."

Jean tells me that one very courageous childhood friend traveled from Penang to Singapore to smuggle a small camera to Roland during his internment in Changi. This was so that Roland and his family could capture evidence of the atrocities taking place.

On liberation day, 1945 when the Japanese surrendered to the Allies, the Japanese Commander in charge of Changi walked down to the public square and took his own life by Seppuku.

Roland tells me that in 1945 after the Allies liberated Singapore and freed the POWs and civilians, some POWs died after being fed too much good food all at once, killed by unwitting acts of kindness.

The biggest problem for the Allies was the sudden influx of people they had to feed and house, now that the Allies had thousands of Japanese POWs, alongside freed citizens and their own troops.

Jean reads from a declaration on how to transition back to civilian life, written on pamphlets dropped from the air, distributed by the Royal Air Force:

"The Japanese forces have surrendered unconditionally and the war is over. We will get supplies to you as soon as humanely possible and will make arrangements to get you out, owing to the distances involved it may be sometime...

You will help us and yourselves if you act as follows; stay in your camp until further orders ... list your most urgent necessities ... if you have been starved or underfed for long periods, do not eat large quantities of solid food, fruit or vegetables at first, it is dangerous for you to do so..."

Roland finally walked out of Changi Prison in September 1945, almost three years after his internment and some months after liberation. On the day of Roland's release and on the back of his internment registration card an autograph is scribbled: Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Roland hadn't see Swan Tin for most of the war. How did it feel to be a free man? Lucky to be alive.

Roland writes to Swan Tin from the Changi/Sime Road Transit Camp. His letter, on Australian Red Cross paper is dated 20 October, 1945:

Roland writes to Swan Tin from the Changi/Sime Road Transit Camp. His letter, on Australian Red Cross paper is dated 20 October, 1945:

"Hello Swan Tin,

Vic and I have just returned from a morning walk when one of the boys told us that they had a letter for me ... well I told him to show it to me first. Before he knew where he was, there was food and there were fags and I read and re-read your letter until I could almost remember all of its words ..."

There was no petrol, no transport. Roland got on a bicycle and somehow made it home to Penang.

After surviving his ordeal in Changi, Roland and Swan Tin reunited and finally married in 1951, six years after the war and after winning-over Swan Tin's disapproving Chinese family.

Image: Swan Tin, Roland's childhood sweetheart and wife

I ask Roland of all survivors of his community, who is left? Jean reminds her father, "All your friends have died now Dad, the only ones left of the camp will be Uncle Vic, Aunty Jessie ... all survivors of Changi have remained friends to this day, until they die. Dad's the last one standing."

Wearing her bright red t'shirt emblazoned with it's iconic image, Jean de Bruyne is a passionate volunteer with the NZ Red Cross. The Red Cross in New Zealand is currently celebrating its centenary.

“New Zealand Red Cross has been part of the fabric of our country for nearly a century. In 1914, at the start of the First World War (WWI), ad hoc Red Cross groups began raising money and sending medical supplies to New Zealand troops overseas. During the wartime effort for both WWI and the Second World War (WWII), New Zealand Red Cross groups worked in conjunction with the Order of St John as a joint council.”

Jean holds up her father's love letters to her mother on the Red Cross paper. These letters were not discovered by the family until two years ago. It is a poignant reminder for Jean. Her parents reconnected through this fragile form of communication. "The Second World War is very, very large in our family psyche. Although we never experienced the war personally its talked about on a constant basis. What the war has done for Dad's generation and our generation is teach us tenacity, the importance of family relationships and the importance of community."

Roland holds up a tiny parcel, dated 11 Jan 1945, 10:30am. It's a fragment of rusted shrapnel from an anti-personal bomber. Roland tells me these fragments littered the ground like snow. Jean shows me a tiny black and white photo taken just outside Changi at the time. It's a public commemoration site, studded with so many white crosses.

Shrapnel from a bomber

Lest we forget. Those that lost their lives to Singapore.

Thank you to Sound Archives for use of the following archival tracks used in the making of this programme.

Thank you to Sound Archives for use of the following archival tracks used in the making of this programme.

Archival audio supplied by Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision.