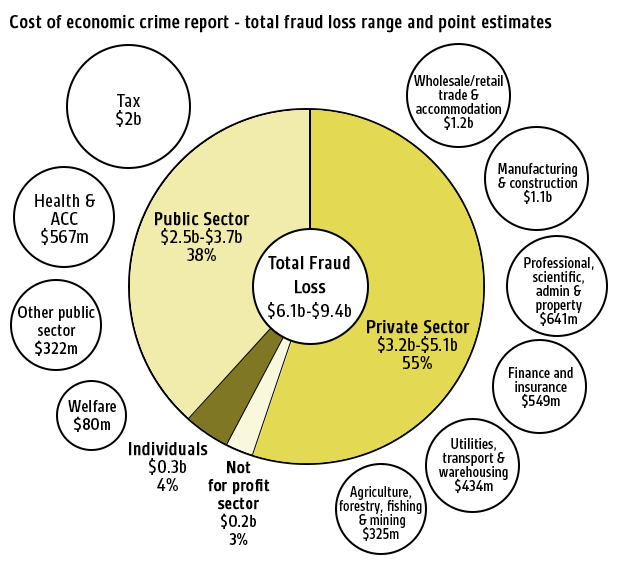

A graphic put together by Radio New Zealand shows some of the estimates in the report.

Photo: RNZ

A draft government report obtained by Radio New Zealand estimates the cost of economic crime to the New Zealand economy is between $6.1 billion and $9.4 billion each year.

We take a look at what’s in the report with criminologist Professor Michael Levi, who helped develop the UK’s National Fraud Indicator which inspired the New Zealand report; Victoria University associate professor Lisa Marriott from the School of Accounting and Commercial Law; investigative journalist Matt Nippert; private investigator Michael Campbell; and Deloitte’s forensic accountant Barry Jordan.

At the beginning of 2013 the then Minister for the SFO, Anne Tolley, was reported as saying that a number of Government ministries had been working for two years on a report quantifying the cost of economic crime and it would be presented to Cabinet in the near future.

But the report did not make it to Cabinet and was not released.

Read the SFO draft report obtained by Radio New Zealand

Radio New Zealand obtained a draft copy of the SFO's report under the Official Information Act. The methodologies that would have made it possible to calculate the total costs were redacted.

However, Radio New Zealand has also obtained a copy of the report with the estimated costs of the various types of economic crime included - which put the total cost of economic crime at between $6.1 and $9.4 billion.

The report noted that was more than twice the combined annual budgets of police, the Department of Corrections, and the courts; more than the total net profit of New Zealand's top 200 companies and top 30 financial institutions; or the equivalent of $2000 for every adult living in New Zealand.

By far the biggest component of that $6.1 to $9.4 billion was an estimated $2 billion a year in tax fraud - benefit fraud by comparison was thought to be about $80 million.

The report estimated that just over $100 million or 5 percent of that $2 billion a year in tax fraud was being detected. The figure was close to 30 percent for benefit fraud.

The $2 billion figure could be on the light side. The Tax Justice Network, an international NGO, has estimated New Zealand tax evasion at $7 billion a year and the IRD itself claimed in its 2011/12 annual report that it had detected $1.2 billion in evasion.

In 2010, the UK National Fraud Authority carried out a similar exercise and estimated total fraud cost £30 billion a year. By 2012 - as a result of "improved methodologies" - the authority estimated the actual figure at £73 billion.

The New Zealand report estimated that fraud in New Zealand accounted for 3.9 percent of the country's GDP. The British report, by comparison, put the figure at 4.8 percent.

Why was the NZ report not completed?

So, why was the New Zealand report not completed? The minister responsible for the SFO, Michael Woodhouse, responded in a statement that he was advised that "the SFO had concerns around the methodology used in gathering the figures, particularly with respect to the calculations being based on measurements from another market".

In a statement to Radio New Zealand, the SFO said:

"The decision not to complete the work was a decision made by the SFO in consultation with other interested Government departments, such as the Ministry of Justice.

"The work previously done to quantify the cost of economic crime in New Zealand was based on a methodology developed overseas. In the course of the work, it became clear that the methodology was not directly applicable to the New Zealand context.

"As a result, the report was not finalised, and there are no plans to continue the work at this time."

In its 2012 to 2015 Statement of Intent, the SFO had made it clear the 'Cost of Economic Crime' report was to play a critical role in the fight against financial crime:

(T)his year, in collaboration with the UK National Fraud Authority, the SFO will complete the first-ever the 'Cost of Economic Crime' report. It will be modelled on the UK equivalent, which has become a core source of information for the UK's financial crime strategies in recent years. This report will be linked to a comprehensive analysis of existing resources, agencies, powers and funding currently devoted to economic and financial crime, and the results being achieved. Together they will provide a map of the current fraud landscape and the basis on which government agencies can report back to the Government on future legislative and operational options for fighting economic and financial crime."

Read the SFO's Statement of Intent

Figures unsurprising - forensic accountant

Criminologist Professor Michael Levi of Cardiff University, who carried out the initial research that led to Britain establishing its national fraud indicator, told Radio New Zealand that the headline figure was not as important as the ability to prioritise which crimes to target.

"In a rational society, given the fact that we can reasonably predict that fraud is a major contemporary crime problem... then why should we prefer to remain in a state of ignorance, except because we just don't want to have to think of other strategies for dealing with a big problem rationally."

A forensic accountant and partner at Deloitte, Barry Jordan, said he was not surprised by the figures reported in the draft SFO report.

Barry Jordan

Photo: Supplied

He said, in general, fraud investigators estimate that fraud accounts for between 3 and 6 percent of turnover.

Mr Jordan said, having observed both the 1987 financial crash and the Global Financial Crisis, he had come to the conclusion that the amount of fraud remained fairly constant no matter what the economic climate.

"Fraud happens whether the economy is booming or is in a low point. There are two aspects that are different: One, the types of fraud happening when you're in an economic high. We tend to see lots of credit card fraud. There's a lot more free money so people just go crazy with the corporate credit cards. The other one is that when you're in an economic low, people's tolerances to economic variables are lower. So you pick up the frauds."

Lisa Marriott, an associate professor at the Victoria University School of Accounting and Commercial Law, has calculated that the 237 cases prosecuted by the SFO since 1984 have had a total value of $681,061,529 or an average of $2.9 million per case.

Lisa Marriott

Photo: Supplied

She said finance company cases were excluded from the calculation as the high amounts tended to distort the overall figure.

Ms Marriott said about 80 percent of those prosecutions resulted in jail sentences for crimes totalling $498,946,294. A total of $15,825,198 in reparations was paid for those crimes.

She has calculated that the average gain for each month of prison per offender is $118,079 or $4000 a day.

"The main point from this exercise is to suggest that there is not a bad 'return' to be made on white collar crime."