“The internet is radically unstable” The mindblowing worlds of Youtube video game essayist Jacob Geller

29-year-old Jacob Geller links games to art and politics through complex narratives and a combination of game footage, film, speaking to camera and a myriad of historical imagery.

If the video game is the 21st century's first great art form, the video essay may be the century's first great new writing platform. That is, if platforms like YouTube stick around for long enough.

American wunderkind Jacob Geller is an enormously popular YouTube video game essayist and art enthusiast.

The mindblowing worlds of video game essayist Jacob Geller

Geller's YouTube channel has had more than 110 million views and over 1.2 million followers. Not bad for someone who in intellect and concerns is essentially an art critic.

It's been estimated there are now five million computer games made in the world. And while video and arcade games have been popular since the late 1970s, the huge growth in their design and creative sophistication, together with the interconnectivity of the internet, marks them out as a leading 21st-century artform.

Computer games are as diverse and experimental in range as art in any other media. They are made by individuals, small independent companies, and giant commercial behemoths alike. In the right artists' hands, the worlds within these games can be mind-blowing in the depth of concept, storytelling and design, as can the size of the online communities surrounding them.

This year the global video game industry is projected to generate about $452 billion New Zealand dollars in revenue. The global industry is already three times the size of the music market, and four times that of the film industry.

It's a market dominated by a younger generation who grew up online. I'm reminded of how, in the late 1950s, kids started picking up guitars and evolving music in ways older people struggled to understand. That was my parents' generation, this is their grandchildren's.

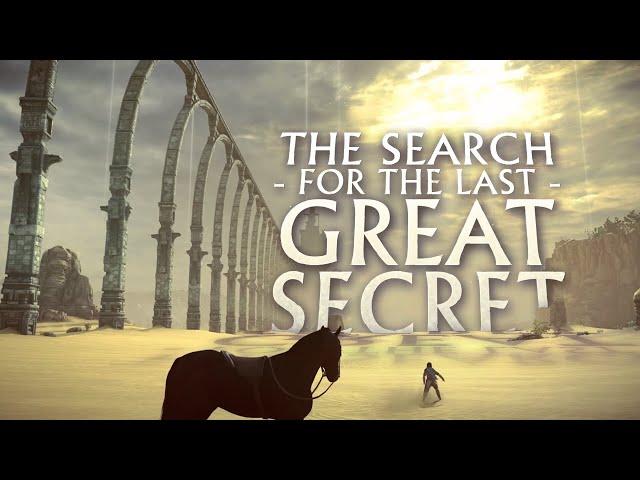

Geller told Culture 101 that his biggest breakthrough happened in 2019 when he made and published a video, The Decade Long Quest for Shadow of the Colissus' Great Last Secret.

The video explored Shadow of the Colossus, a 2005 PlayStation action and adventure game. An immediate hit, the video racked up 2 million views in the first month and generated a whole new audience which became interested in his back catalogue.

Geller's approach is smart and engaging. I'm reminded of the listener engagement on podcasts like NPR's This American Life. Here, however, you also get moving images akin to a traditional television documentary in the vein of art historian Kenneth Clark's seminal 1969 series Civilisation or John Berger's 1972 BBC response Ways of Seeing. As Geller admits, there's nothing new here, but the topics he chooses and his viewership certainly are.

The video essays focus on more than gaming. Thematically based, Geller links art, history and politics. He's introducing gamers to worlds beyond their screens, and the non-gamers - like myself - to the richness of gaming, as well as ideas with contemporary currency.

An example. In the 2023 video essay Art in the Pre-Apocalyse, Geller moves from a spectacular fight scene in the 2023 action game Final Fantasy 16 to Neville Shute's iconic 1950s Australian novel and film On the Beach (a favourite of my father's).

He quotes the REM Gen X anthem 'It's the End of the World as We Know It' while connecting to the skater punk aesthetics of a 2020 'photography simulation' video game Umarangi Generation developed in Tauranga. He relates this to the 2019-2020 Australian Bushfires and an arcade game made at the height of the Cold War, 1980's Missile Command.

Other Geller viral favourites include What is Art to a Fascist and an essay comparing the design of shooter video games to the architectural renovations at Sandy Hook Elementary School in the United States, following the horrific 2012 mass shooting.

The video essay is a strong new writing form partly because of another hugely popular cultural pursuit in the 21st century: watching others play video games. Game streaming website Twitch, for example, say they have an average 2.5 million viewers watching others play games at any one time.

Why would you want to do that? Some of you may ask. Well: why watch other people play cricket for five days? Viewing, rather than playing a video game, gives you more opportunity to check out the scenery. The art. And to be that armchair critic.

As we view Geller's work, we are like pillion passengers on the back of a motorcycle, introduced to multiple rich new online worlds as well as ideas. When considering the concept of haunted houses in games, literature and film, for example, Geller looks at Japanese myths around goblins moving into abandoned houses, and the Jewish tradition of calling a rabbi to cure a house of its own internal leprosy.

In Who's Afraid of Modern Art: Vandalism, Video Games, and Fascism, Geller moves from the destruction of a minimalist painting by Ad Reinhardt at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam to a free experimental computer game 2:22am. Then it's onto Senator Jesse Helms's exhibitionary tactics with Robert Mapplethorpe's photographs, and the Nazi's 'Degenerate art' exhibitions.

Geller's videos often meditate on how we live, both on and offline, as we build anew with the ever-present danger of forgetting our rich cultural past. He starts his essay After a City is Buried considering the city of Kaifeng in China that, first destroyed by flood in 1642, has been rebuilt on its own ruins six times over. This leads to a discussion of the 2021 video game The Forgotten City where players can disappear into the ruins of past cities underground.

Geller's essays remind us that while game developers relish the opportunity to constantly expand into new territories, in the real world land use has been based on colonisation and resource depletion. 2023 essay Games That Don't Fake the Space features a 2009 Playstation and Xbox racing game Fuel where players can drive freely for hours out into a territory the size of Connecticut.

For the essay Art for No One, Geller considers 'City' by Michael Heizer, a gargantuan land artwork in Nevada that is in some ways akin to an enormous physicalisation of a computer game environment. It was Heizer's labour of love for 50 years, yet no photographs are allowed at 'City' and only 460 visitors a year are allowed to visit, their names drawn annually through a lottery.

Geller connects this to the now-famed 19th-century Black paintings of Francisco Goya, which he painted on the walls of his home, and then covered. Then onto the musician Prince, locking away his recordings in a vault in Paisley Park that only he had the access code for.

The greatest irony with this successful YouTuber is that he is now publishing a book.

Due to be published early next year, How a Game Lives re-examines ten of Geller's most iconic essays, with extensive annotations and accompanying essays by other writers.

Earlier this year Geller opened preorders to crowdfund the book's production. Aiming to raise US$60,000, before the campaign closed he tells Culture 101 they'd made US$900,000. This was a way for his fans to pay back for the years of work he had delivered to them.

Publishing a book follows Geller's certainty that YouTube won't be a repository for his work forever.

In his video essay, How can we bear to throw anything away? Geller muses on our ability to hoard enormous numbers of drafts and other material digitally rather than discard them. At the same time, he notes a report that 87% of classic computer games (those from before 2009) are no longer available to most people. A percentage higher, he notes, than early silent movies.

How long will Spotify actually last, he muses. What about Wikipedia, compared to the lifespan of his grandparent's bound encyclopedia?

Keeping everything doesn't make it more accessible. Geller fully expects what we have access to on YouTube will fall to commercial interest or disinterest.

"The internet is radically unstable," Geller surmises. "There are many ways things can be lost"